Haddad: How Allied POWs were saved by a glider that never flew

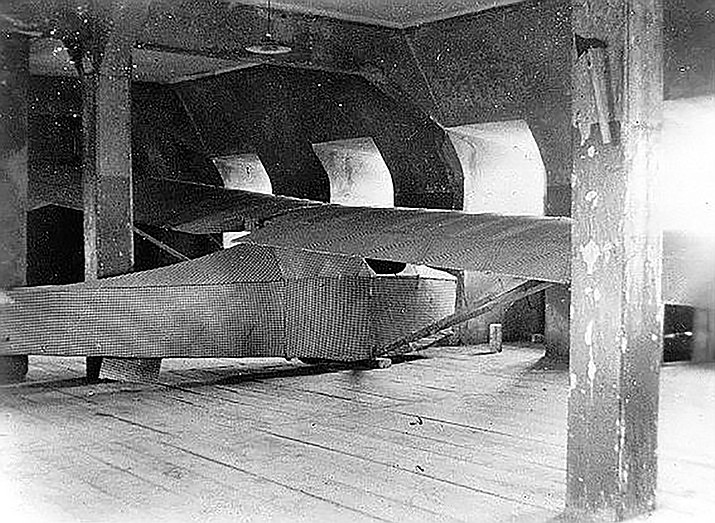

Stolen bed slats and floor boards from the prison were used to construct the ribs and frame of the plane. Electrical wiring from unused portions of the castle were fitted as rudder and elevator control wires. The skin of the glider was made from sleeping bags sealed with boiled ration millet. (This is the only known photograph of the original glider taken on 15 April 1945 by Lee Carson, one of two American newspaper correspondents.)

On the crest of a tall ridge in the German town of Colditz stands a Renaissance castle. The immense fortress played an important role as a lookout post for German Emperors during the Middle Ages. But during World War II the role of the castle walls was reversed when the Germans used Colditz as a prisoner-of-war camp.

It became known as camp Oflag IV-C, a prison designed for Allied POWs who had repeatedly escaped from other prison camps.

One of the prisoners was Tony Rolt, a young British Lieutenant. He discovered that the chapel roof line was completely obscured from the view of their German captors. Rolt hatched a crazy plan to build a glider that could be launched from the roof and fly two men across the Mulde River 200 feet below.

Rolt enlisted the help of pilots Bill Goldfinch and Jack Best, and 12 other men dubbed the “apostles.” They built a secret workshop behind a false wall in the lower attic above the chapel and set in motion what seemed like an impossible task. They placed lookouts and even created an electric alarm system to warn of approaching guards. They were aided by the discovery of a book in the prison library called Aircraft Design, which provided illustrations explaining flight physics and engineering.

Stolen bed slats and floor boards were used to construct the ribs and frame. Electrical wiring from unused portions of the castle were fitted as rudder and elevator control wires. The skin of the glider was made from sleeping bags sealed with boiled ration millet.

The result was a lightweight, two-seater, high wing monoplane glider with a 32-foot wingspan.

The plan was to launch the glider using a gravity-assisted pulley system attached to a falling bathtub filled with cement.

Everything was set. The plane was about ready, take-off dates were considered and by all accounts Rolt and his team were about to do something that had never been done. But then, on April 16, 1945, American troops liberated the camp and the glider was left behind.

Someone hearing this story might have been expecting a much grander finish — such as two prisoners taking a glorious flight to freedom. But more than two men were saved by the airplane that never flew.

In the case of the Colditz Glider, the very act of building the plane became a means of escape for the men of the prison camp. It not only lifted morale and sharpened minds and bodies, it strengthened their will to survive and gave them hope and direction. The lives of the men reflected the success of the glider long after the plane was lost to history.

Tony Rolt became a well known race car driver and founded a research company instrumental in the development new race car systems.

Jack Best was appointed a member of The Order of the British Empire and served the people of Kenya where he had grown up as a child.

These men and others not only survived, they thrived. And they left us an amazing tale of ingenuity and courage.

So was Rolt’s crazy plan a failure?

Oftentimes our own expectations of success can blind us. With all we invest to write our own stories in life we must be willing to trust that failures and trials are all parts of true success when measured on the scale of eternity.

“Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts.” — Winston Churchill

Epilogue: In 1999 a full-sized replica of the Colditz Glider was commissioned by a British television station. Best, Goldfinch and a dozen of the veterans who had worked on the original plane proudly looked on as it was flown successfully on its first attempt.

Richard Haddad is Director of News & Digital Content for Western News&Info, Inc., the parent company of The Daily Courier. This column originally appeared as a blog entry on dCourier.com.

Related Stories

Sign up for our e-News Alerts

SUBMIT FEEDBACK

Click Below to: